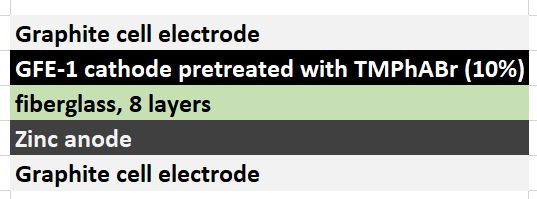

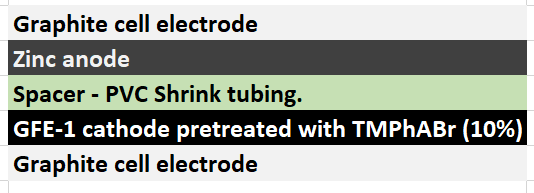

In my previous post, I described my first tests of separator-less batteries using a PVC spacer. This turned out not to be a very good idea, due to the reactivity of PVC with bromine. Although the battery was able to run for 20+ cycles successfully, a lot of noise started to happen within the measurements. After opening up the battery, it was evident that the separator had degraded (it turned from black, to a whitish gray color). Due to this reactivity I decided to change my plans to work with Teflon o-rings as spacers (which I bought here). These are of the exact diameter I needed. Given the height of the spacers, I decided to use 3 (total height of 5.2mm) in order to match the same height of the previous cells I was building using fiberglass separators. This gives a total battery volume of around 0.68mL, counting the volume of the separators.

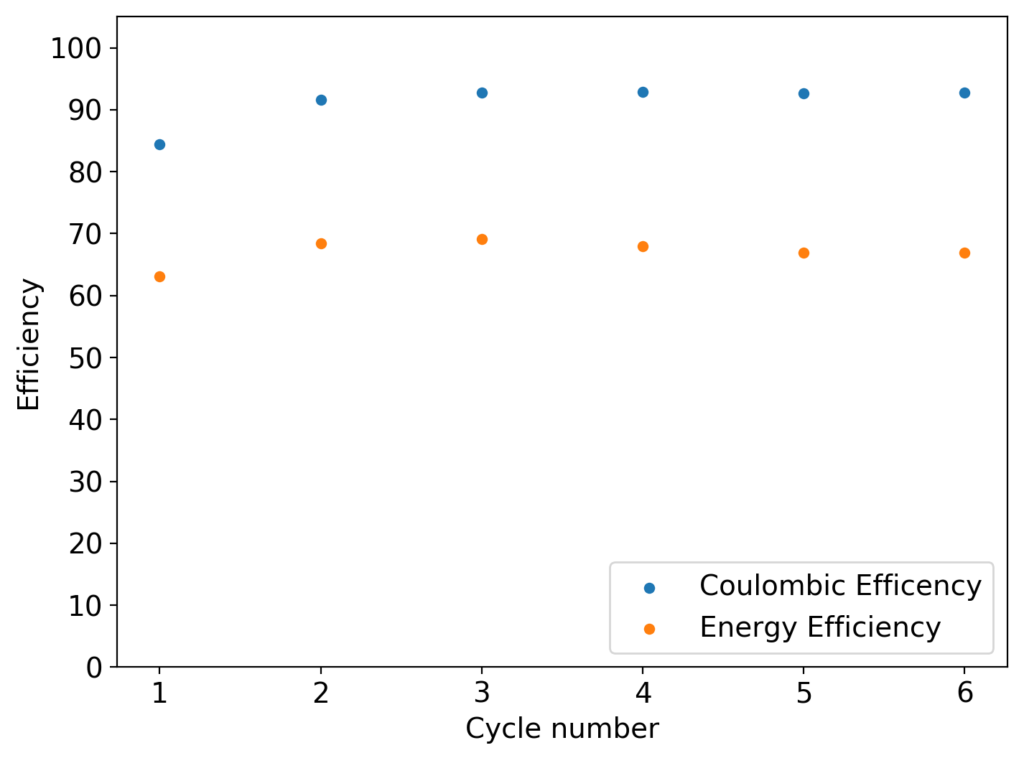

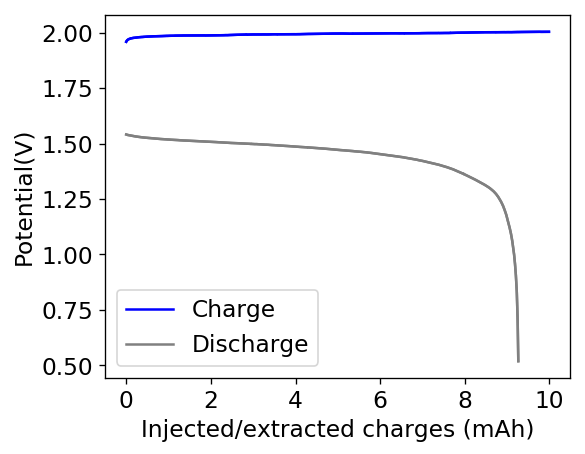

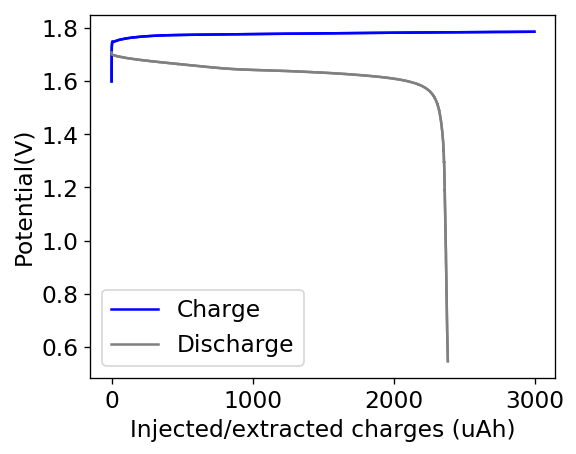

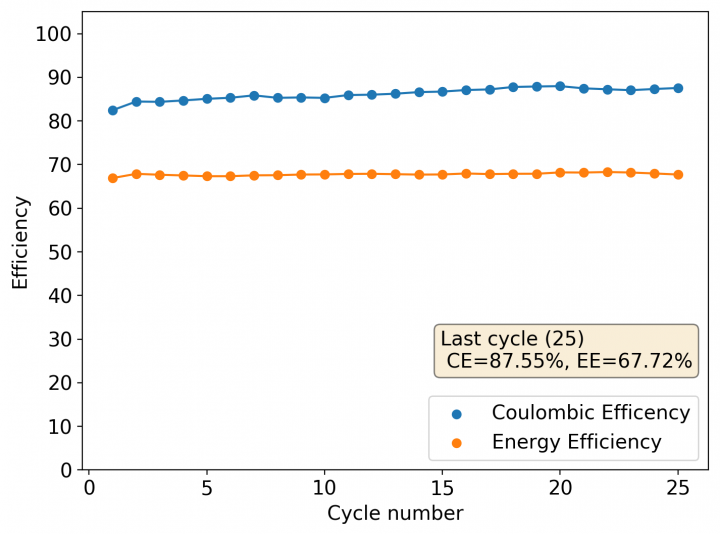

The results for the first battery tested using this configuration is shown above. The energy density of this battery is around 30Wh/L and I was able to cycle it at this current density and charge capacity for 25 cycles without running into any problems or instabilities. At this point I decided to test what the maximum capacity of the battery could be, by charging the battery until the potential reached 2.1V.

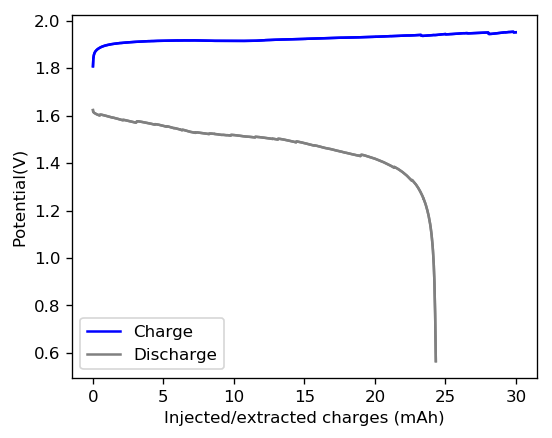

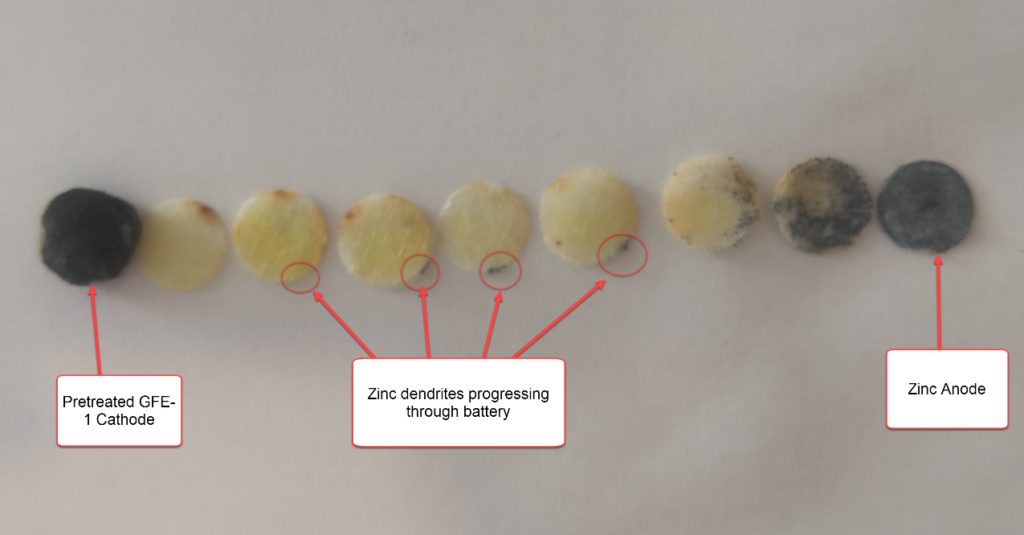

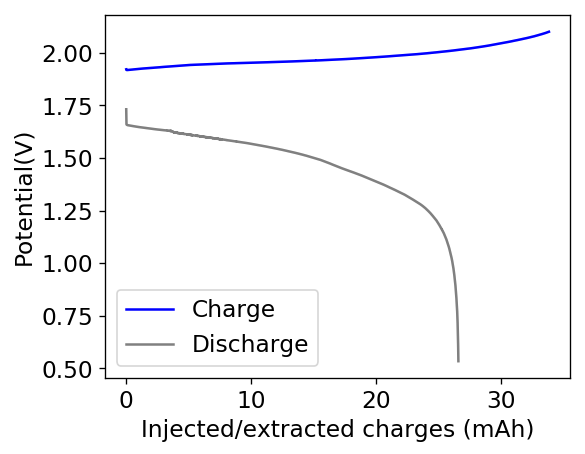

With this test I was able to charge the battery to a capacity of around 60Wh/L, but this capacity usage is not sustainable given that the battery completely died on the next cycle due to the formation of a large amount of Zinc dendrites. This means that the usable capacity under this amount of 3M ZnBr2 electrolyte is likely to be around 75% of this value – given what we know from published research and patents – which should be at least 25mAh.

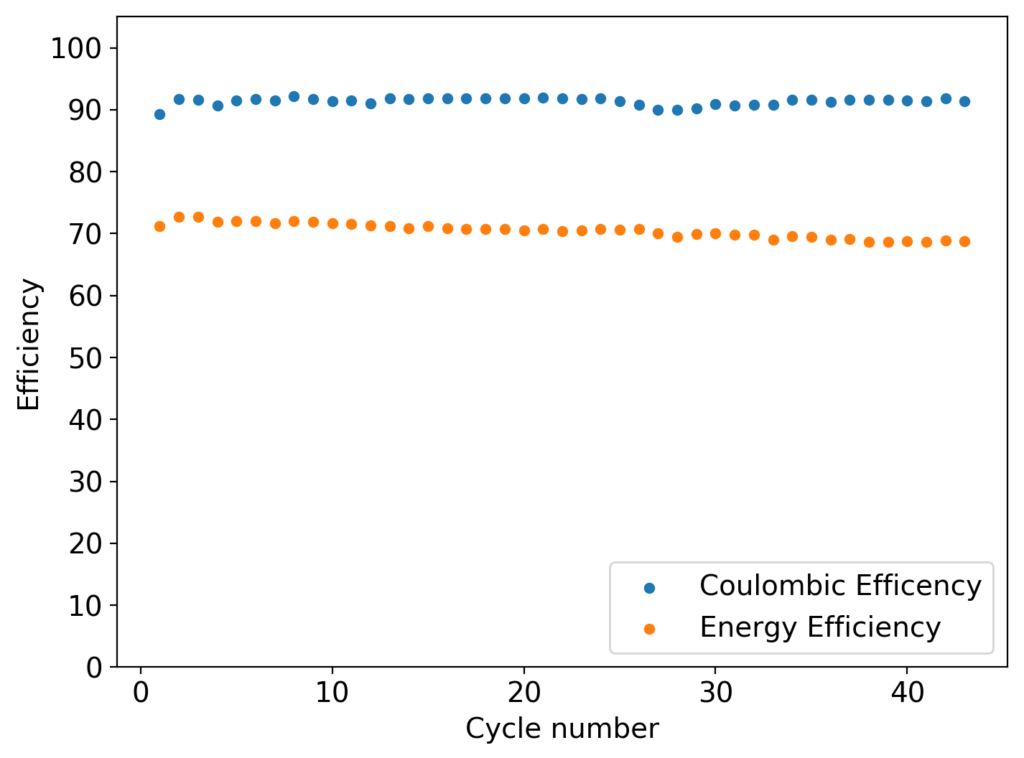

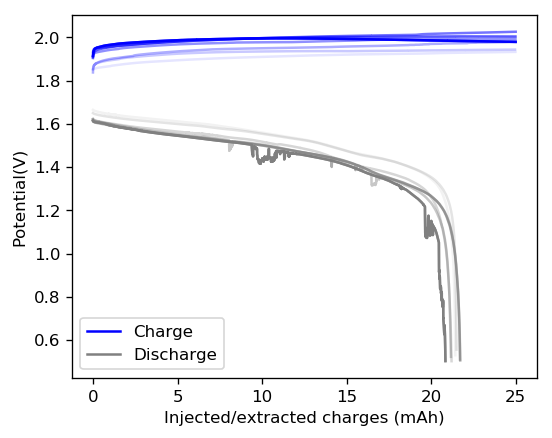

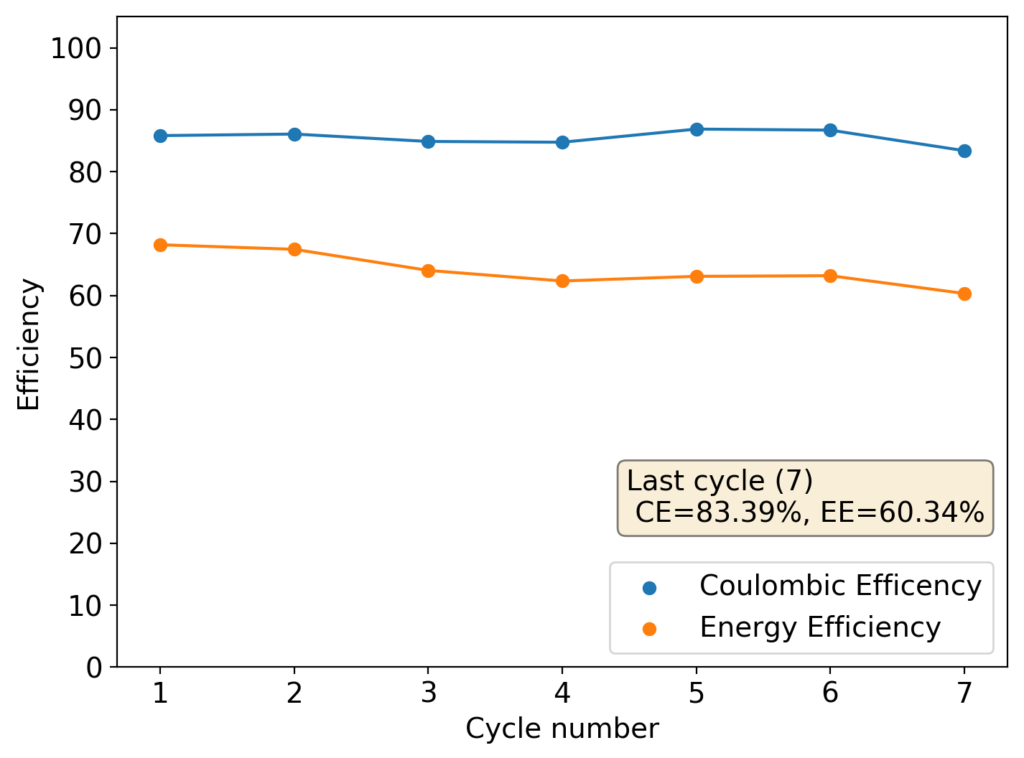

After building another battery and charging to 25mAh – taking the energy density to ~45 Wh/L – there were substantial instability issues appearing on the discharge curves after 7 cycles. I believe these instabilities are due to Zn dendrites that fall from the anode into the cathode, temporarily killing the discharge potential of the device until the Zn dendrite is dissolved. These instabilities are correlated with loses in both the Coulombic and energy efficiency values of the battery, deteriorating the performance as a function of time.

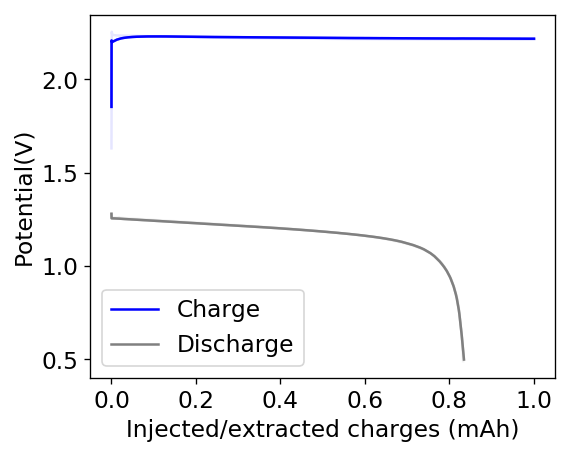

Due to the above issues, it seems important to try to reduce dendrites to prevent problems at these capacities. I decided to try a PEG-200 additions at 20% to see what would happen. With this configuration, a 20% PEG-200 addition generated too much voltaic loses because of the huge increase in internal resistance. Even when charging/discharging to only 1mAh, the necessary potential was already above 2.15V, with the energy efficiency dropping below the 35% mark. You can see one such cycle in the image below.

Because of the above results, it is clear that a PEG-200 addition is likely going to need to be below the 10% mark in order to be viable. I have since prepared an electrolyte comprised of 3M ZnBr2, 6% PEG-200 and 0.1M NaCl in order to see what the behavior is when trying to charge to these higher capacity values. Up until now charge potentials at 15mA are higher than for the 1% PEG-200 cells, but low enough (2-2.1V) to prevent heavy voltaic loses. We’ll see what sort of efficiencies and Zinc deposits we can get with this electrolyte configuration.