All-Fe flow batteries are very promising due to iron’s high abundance, low toxicity and low cost. In these batteries, FeCl2 is used as the main active salt in solution. When charging Fe2+ gets reduced to Fe metal on the anode while Fe2+ gets oxidized to Fe3+ on the cathode. However, these batteries suffer from a fundamental problem that has made their large scale adoption very difficult up until now.

The main limiting problem of these batteries is H2 evolution at the anode. Since Fe plating happens at a lower potential than H2 evolution, there is always some hydrogen generation when the battery is charged. This H2 evolution causes an increase in the pH of the battery which then causes iron hydroxides and oxides to precipitate out of solution. This causes passivation of Fe metal surfaces, loss of capacity and potentially clogging of the battery.

A few years ago, Tao Gao’s group in Utah discovered that CaCl2 and MgCl2 water-in-salt-electrolytes (WiSE) (read the paper here) could substantially improve Fe plating behavior. While they didn’t test this in flow batteries, they showed that very high Coulomb efficiencies with very low hydrogen evolution rates were possible when using these salts. This is because these salts bond with water and therefore make it substantially harder for water to get reduced at the anode. We are talking about very highly concentrated solutions though, around 4.5M CaCl2, which is around 660g/L of CaCl2.2H2O.

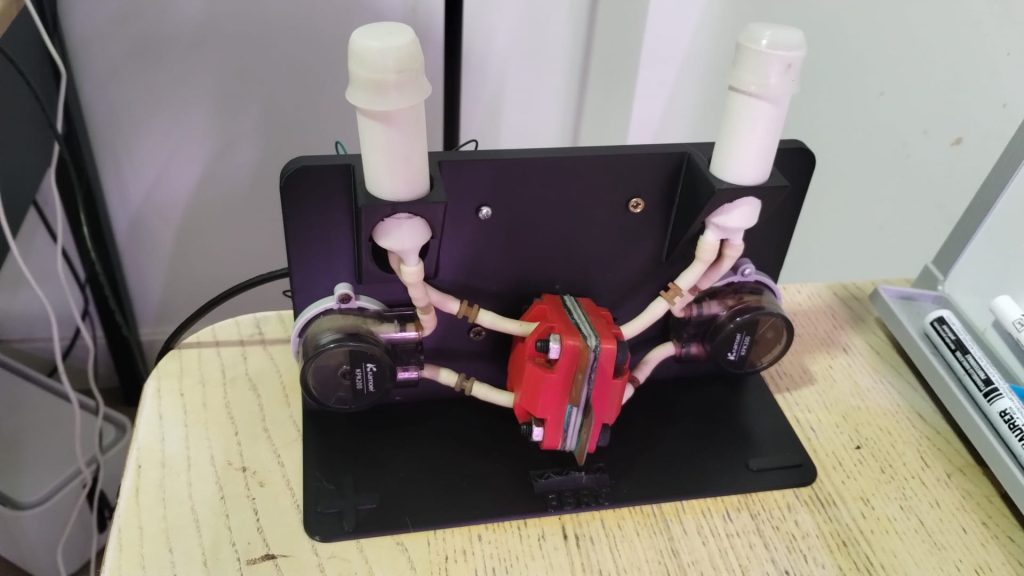

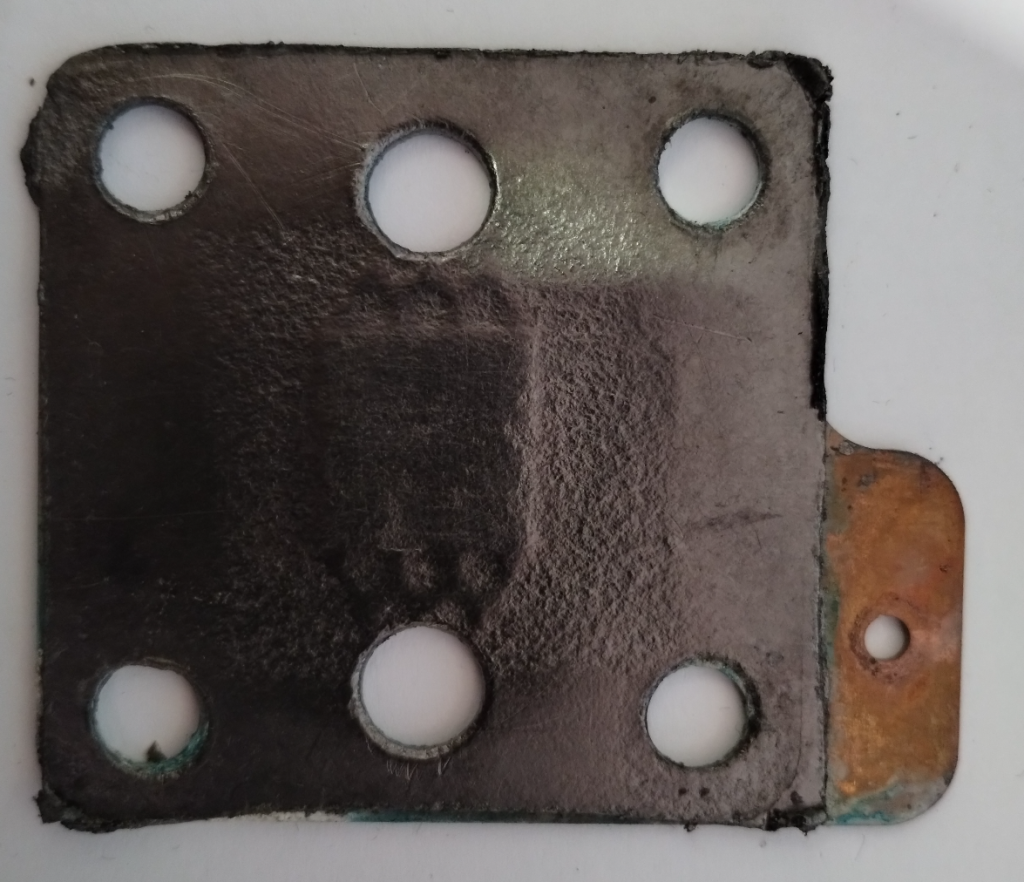

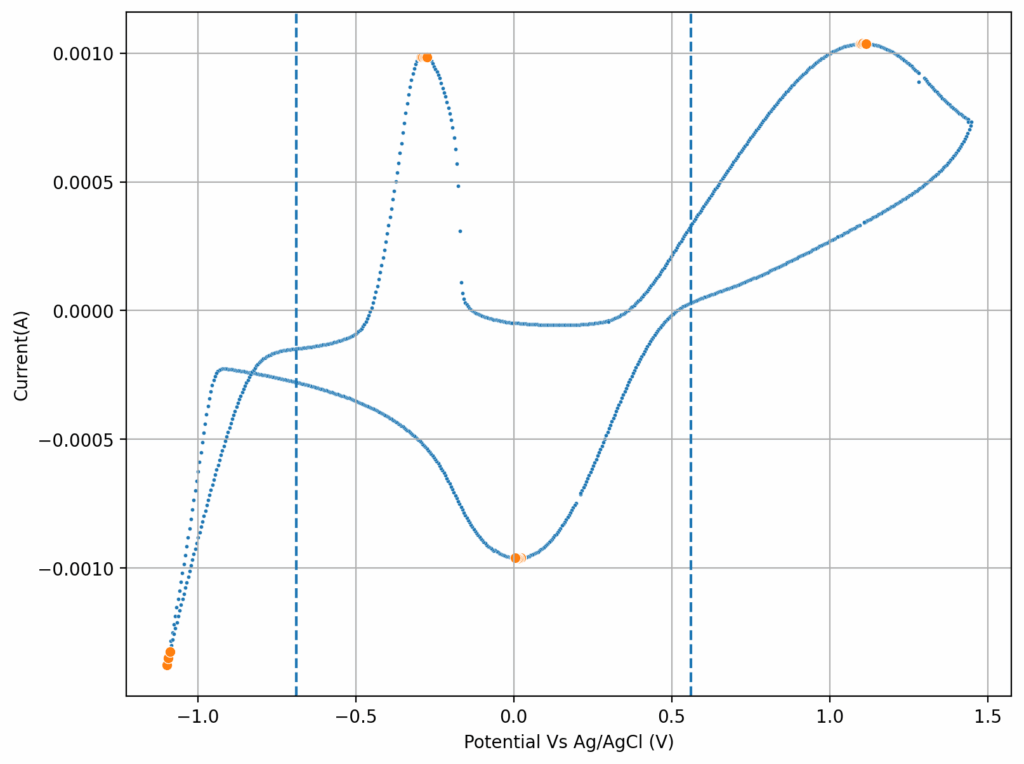

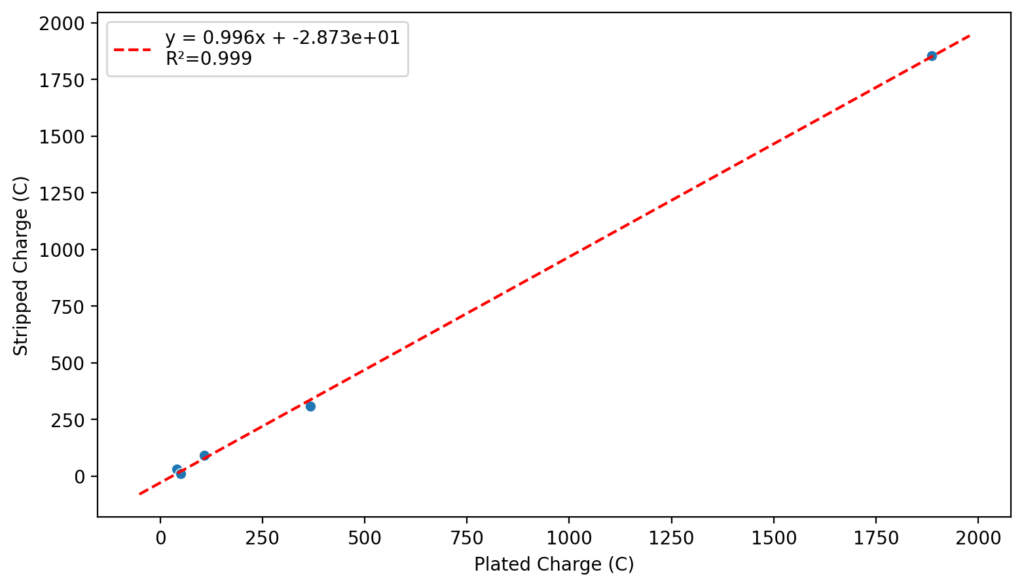

We recently obtained some of these reagents to test these chemistries in our flow battery kit. I first ran CV experiments of the 4.5M CaCl2 electrolyte with 1M FeCl2 and obtained the curves showed above. This reveals standard potentials of -0.71V and 0.55V for the two half reactions, which means our battery should have a max potential of around 1.26V. I then ran plate/strip experiments (using different plating times), which generated the second curve above. Using the slope of this plot we can extract the plating efficiency, which is >99% in this case. This means that very little hydrogen evolution is happening within this electrolyte, a result I had never seen with FeCl2 solutions and which is in agreement with the Tao Gao group paper.

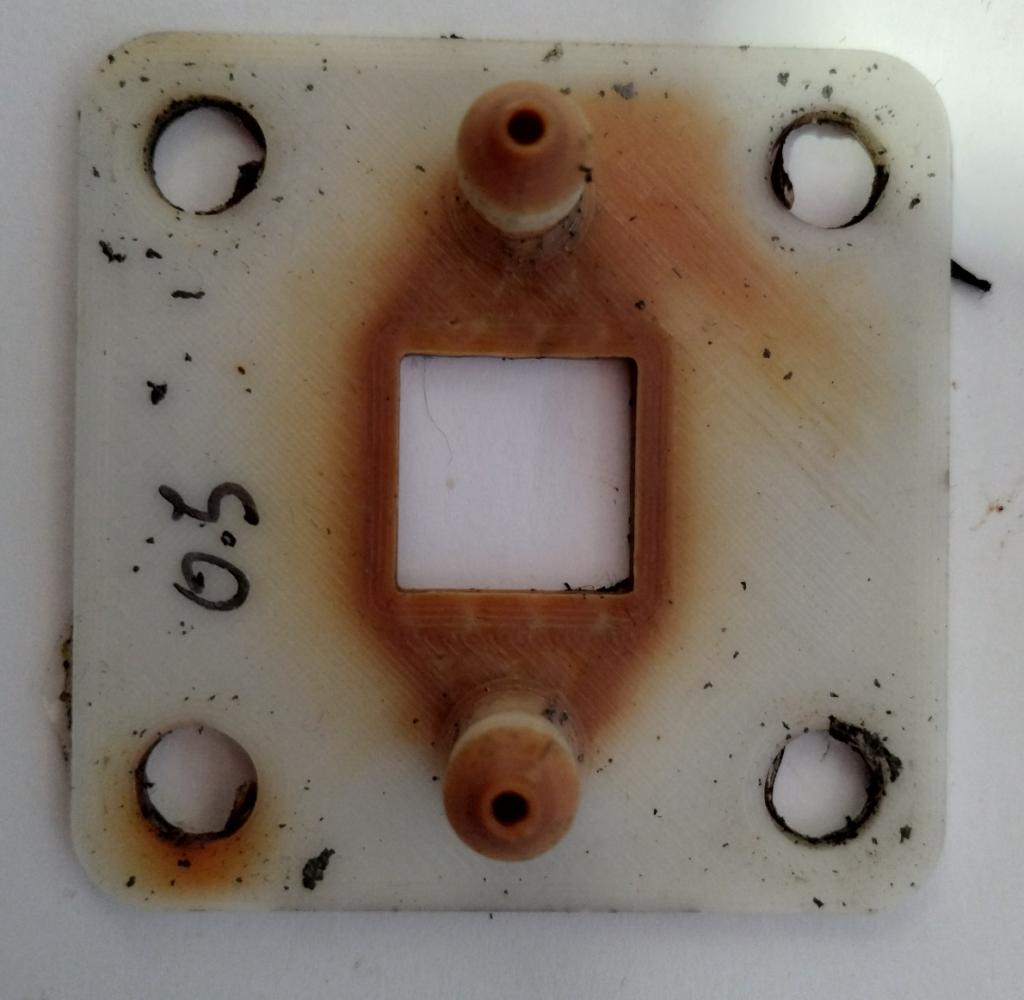

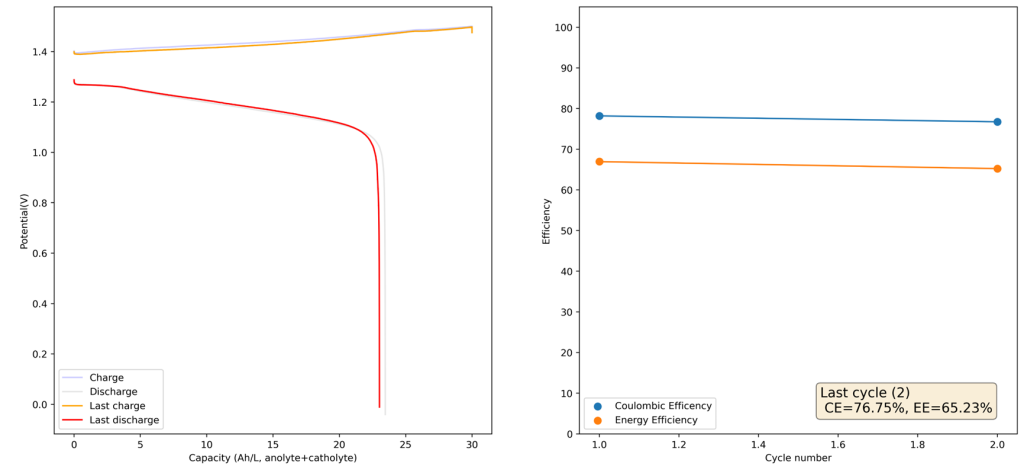

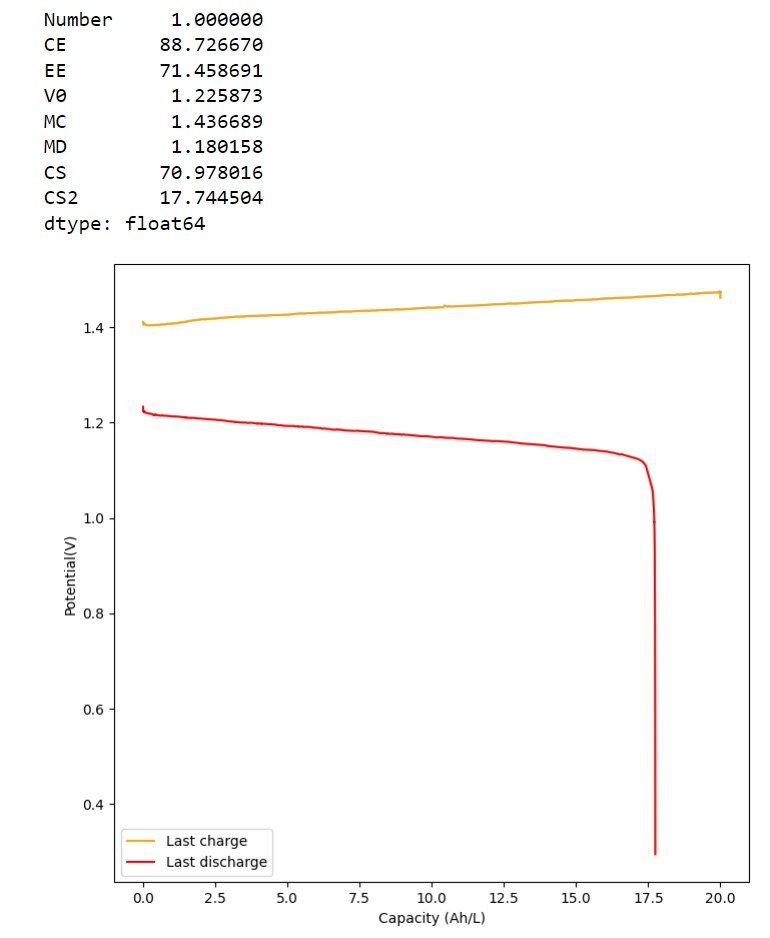

After doing this I then ran a flow battery using this electrolyte and noticed some problems with capacity loss because of undissolved metallic Fe on the anode using a Daramic separator. It seems that the above electrolyte has some issues with the reversibility of the plating reaction. While little hydrogen is generated on plating, there still seem to be some important losses of capacity due to passivation of the Fe. To fix this problem I then added 1M NH4Cl into the electrolyte, which helped me fix this issue when dealing with Zn-I flow batteries.

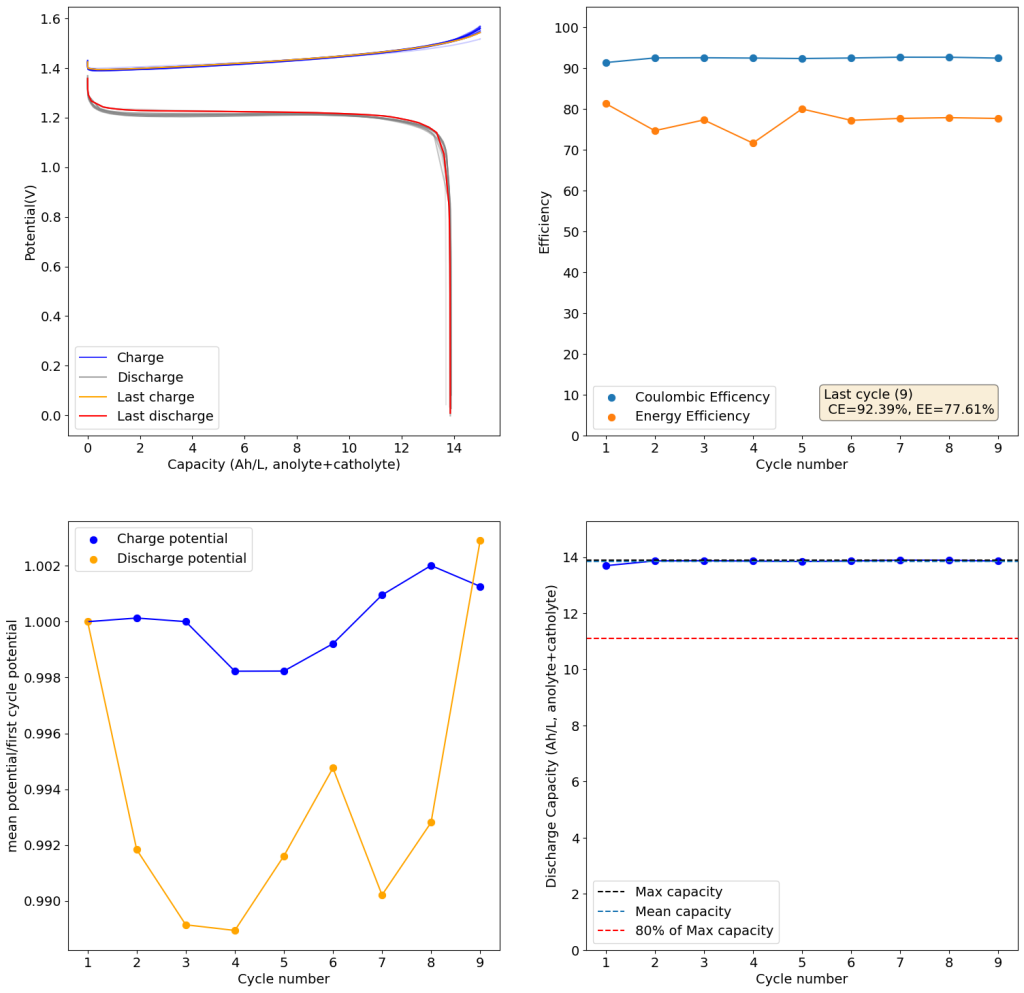

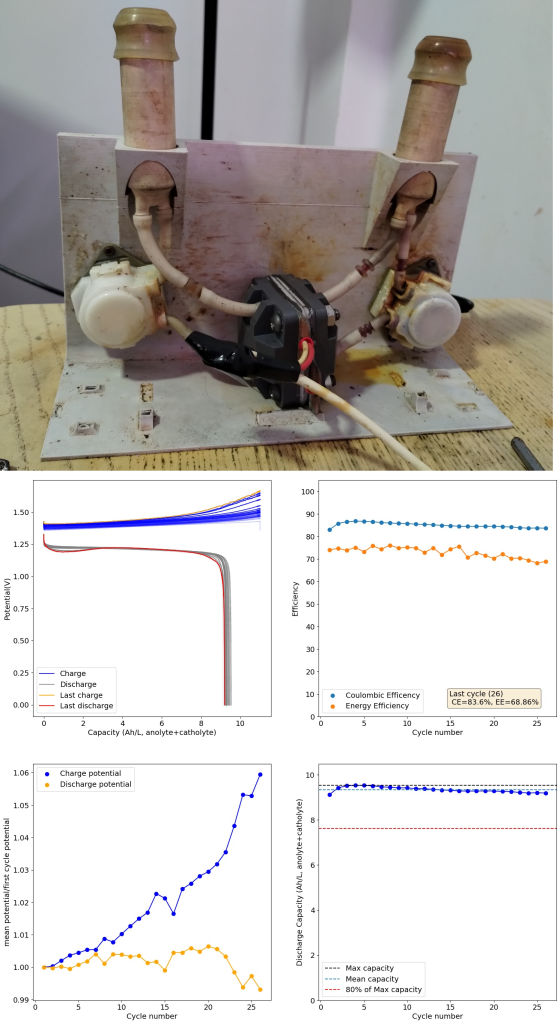

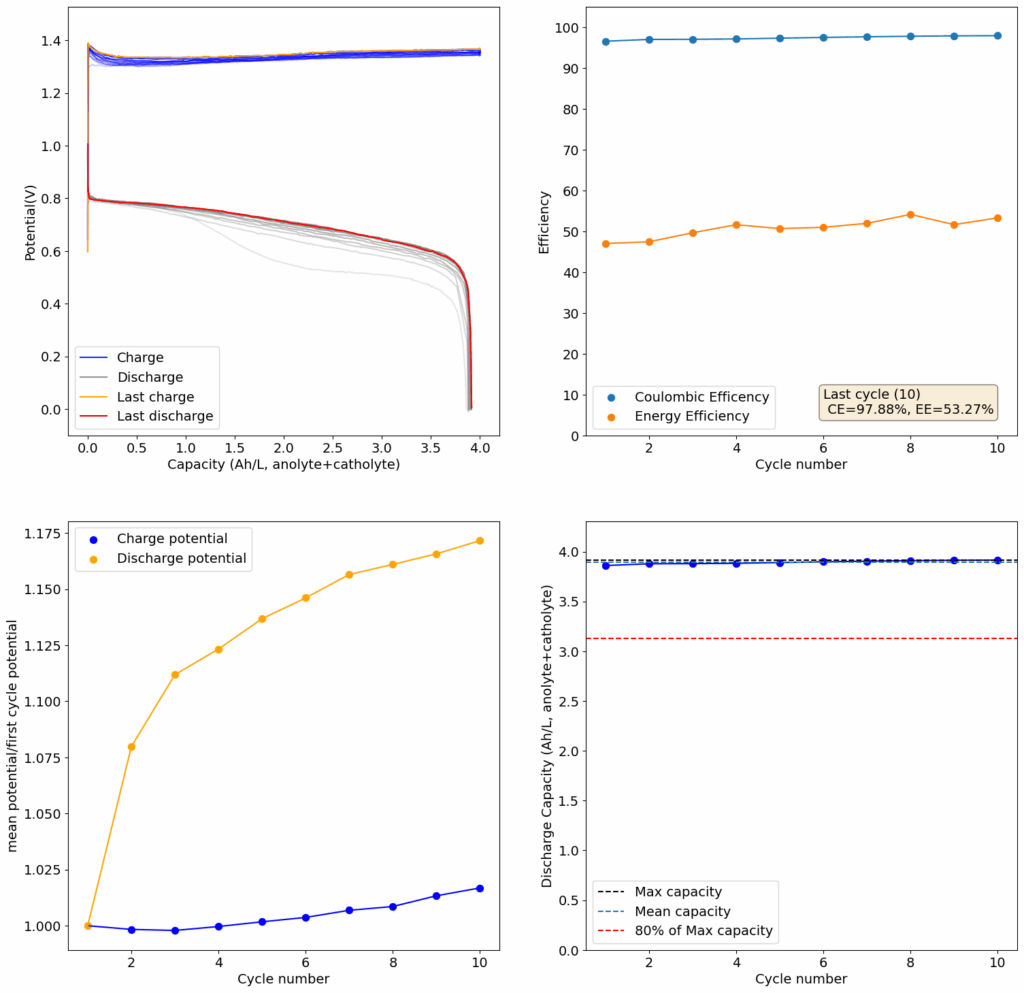

I cycled the battery at 4Ah/L, which generated the results above. You can see that we get extremely good CE values (97.88%) which are even better than those we were obtaining with the Zn-I system, even though we’re using a microporous separator. The energy efficiency is lower than for Zn-I but still reaches a value of 53.27%. Given a concentration of 1M FeCl2 , 4Ah/L represents a state-of-charge (SOC) of ~30%. The cycling is stable, although some increase of the charging voltage is indeed happening through time (although this is also matched by an increase in the discharge voltage). The mean discharge potential is quite low though, at 0.7V, which means we have considerable ohmic losses at this current density.

I am now testing the electrolyte at higher SOC values and will continue testing MgCl2 and other modifications, such as additions of ascorbic acid and thiosulfate to remove oxygen from the initial solutions and improve the initial state of the battery (as some capacity is lost due to the presence of oxidized Fe in the initial solution). Make sure to follow our progress on this forum thread.

This flow battery kit work is being funded by the Financed by Nlnet’s NGI0 Entrust Fund. We are also collaborating with the FAIR Battery project.