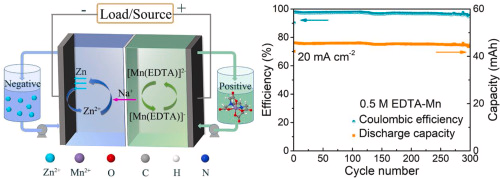

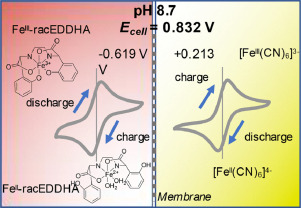

During the past couple of weeks I have been working on cation exchange membranes using PVA/cellulose (see here, here, here). The idea is to create a membrane that can replace Nafion in a pH neutral flow battery built using an Fe anolyte and a Mn based catholyte. In this post I will share the first results that are up to par with those of a Nafion membrane.

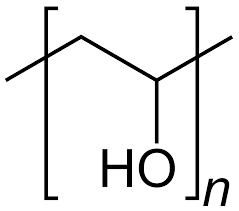

My initial idea was to both crosslink and add anionic sites to the PVA by using phosphoric acid with urea as a catalyst, heating the membrane to >150C in order to perform the esterification process. This worked to a decent degree, achieving membranes with permselectivity values above 80% with sheet resistance values around 10x those of Nafion membranes.

However there were some obvious issues with this process. The first is that the membranes produced had some stability issues, their permselectivity would drop with time – due to lack of enough crosslinking – and the mechanical stability of the membranes also left a lot to be desired. Both of these issues were likely due to limited crosslinking of the membranes, as forming a double phosphoric acid ester is not a very favorable process, even in the presence of urea.

I would see Fe-EDDHA-1 leak across the membrane within around 24 hours of setting up my cells, with the transparent side turning a slight pink within that timeframe. The permselectivity would also drop from 80% to around 40% within that timeframe. It was obvious that these membranes had components that were still dissolving or at least creating cavities that allowed too much water to flow through.

Thinking about this, I searched for possible crosslinking agents to enhance the issue. I also wanted to avoid usage of anything toxic, like glutaraldehyde, as the space where I carry out these experiments has limited ventilation, plus I want to avoid exposing myself or my cats to harmful substances. Expensive substances were also out of the question, like sulfosuccinic acid.

Reviewing papers on the subject, citric acid appeared to be a viable substance. It is a tricarboxylic acid, so it would be able to crosslink cellulose with PVA, PVA or cellulose with themselves and also keep some exposed anionic carboxylic groups to provide cation exchange capacity. Adding phosphoric acid would also catalyze the esterification reaction plus also provide some phosphorylated sites for enhanced permselectivity.

The process for preparing these membranes is as follows:

- Prepare a solution by adding 15g of PVA to 200mL of water (solution A).

- Place solution A in a fridge for 48 hours, with occasional stirring/shaking. Surprisingly, cold conditions are much better for dissolving PVA because they discourage agglomeration.

- Wait till solution A is fully homogeneous, keep longer in fridge and shake/stir as needed.

- Prepare another solution by using 0.5mL of phosphoric acid (81%), 0.5g of citric acid and 15mL of solution A. This solution is stirred until everything is completely homogeneous (solution B).

- Dip a filter paper in Solution B. I used Stony Lab 101 but other fine grain filter papers should work just as well. Make sure all excess has dripped off and tap with paper towels to remove any excess.

- Place on a hot plate at 80C for 3min

- Flip it to the other side for another 3 minute.

- Use a brush to paint solution B on the filter paper while on the hot place.

- Wait for 3 minutes.

- Flip the filter paper and paint the other side, wait another 3 minutes.

- Repeat steps 8-10 three times.

- Increase the temperature to 150C.

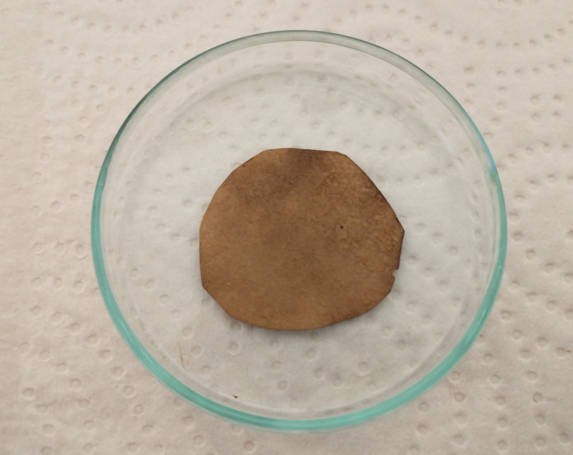

- Flip the membrane every 10 minutes for one hour or until the membranes appear fully black. Put a petri dish on top if needed to keep the membrane flat.

- Allow the membrane to cool to room temperature.

- Place the membrane in a solution with 10g/L of potassium or sodium carbonate to neutralize any remaining acid, they can be stored in a 0.5M NaCl solution.

The membranes that result from this process are black in nature. However they do not feel like charcoal and do not crumb easily. Instead, they have the feeling of a piece of plastic film, which is exactly what we are looking for. Several papers discussing citric acid crosslinking of different polymers do have resulting black films, so this isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

I was also very pleasantly surprised by the permselectivity measurement for these membranes. Measuring the potential across NaCl 0.1M | NaCl 0.5M using identical Ag/AgCl reference electrodes, the potential is 38-39mV, meaning that these membranes have permselectivity values >99%, which is equivalent to that of the best Nafion membranes. Adding 0.01g of NaFeEDDHA to the NaCl 0.5M side – which makes it dark red – I could see absolutely no crossover of FeEDDHA-1 to the other side of the half-cell experiment within 48 hours of testing. There were also no drops in the permselectivity which remains extremely high. The sheet resistance measurements are also very favorable, with in place sheet conductivity values now in the <50 ohm/cm2 range.

Overall, I am pleased with this DIY membrane result. The crosslinking of PVA using citric acid and phosphoric acid on a cellulose matrix provides you with a very robust membrane that has some wonderful characteristics. This will be my base membrane for the construction of Fe-Mn flow batteries. This membrane is also very low cost.