As my avid reader Giancarlo pointed out in the comment section a few posts back, many of the big problems of the Zn-Br battery system seem to be caused by the use of an aqueous electrolyte. Hydrogen evolution and voltaic losses due to the use of insoluble or immiscible bromine sequestering agents are some of the biggest issues that are inevitably related with water. Changing to a non-aqueous solvent can help solve some problems, although some others are created.

An organic solvent to replace water in Zn-Br batteries would need to be aprotic and to allow for the creation of substantially conductive solutions using ZnBr2. The issue with these organic solvents is that they are also extremely friendly to bromine, most of them being infinitely miscible with elemental bromine. This means that a battery built using these highly polar, aprotic solvents, would discharge significantly faster, as bromine would be significantly more likely to migrate to the anode. Sequestering agents would not be usable as these agents and their tribromides are incredibly soluble in these solvents as well.

However, this property can be exploited to solve part of the problems of the Zn-Br battery, at least the part dealing with voltaic losses related with the sequestering agents in water. This paper from 1988 shows how propionitrile can be used within a battery to sequester bromine and prevent its migration through the cell. In this device, an aqueous anolyte is used with an organic catholyte to trap bromine near the cathode. Since bromine has such a high affinity for propionitrile it will tend to stay in the organic section of the device, preventing movements towards the aqueous layer and providing more efficient confining and higher conductivity compared with some common sequestering agents. This is the only paper I could find that discusses the testing of Zn-Br batteries with a non-aqueous solvent that is not an ionic liquid. There are however, no papers I could find where the anolyte is replaced by an ionic liquid as well.

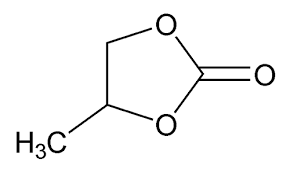

Propionitrile – and nitriles in general – are nasty solvents though. They are significantly toxic and we wouldn’t want to use them for DIY home batteries due to these issues, especially if we’re going to be experimenting and having close contact with their solutions. For this reason I will avoid their use and will instead use the non-toxic aprotic polar solvent, propylene carbonate. This solvent can also be bought pretty easily on the internet (I got mine here).

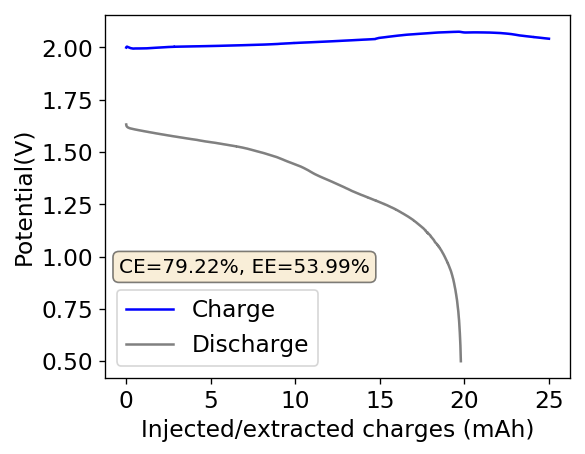

Propylene carbonate can form highly conductive solutions with some salts, it is reasonable to predict that both the quaternary ammonium salt I have (TMPhABr and TBABr) will be soluble in it, as well as ZnBr2. I have no idea about whether Br2 or perbromides are soluble in it though, but it is reasonable to expect Br2 to be highly soluble in it because of how other, similar solvents, behave. There is some precedent for a battery fully constructed with a metal bromide using entirely propylene carbonate, see this paper, so it might actually be possible to use propylene carbonate by itself, although this is probably not possible without a suitable membrane separator.

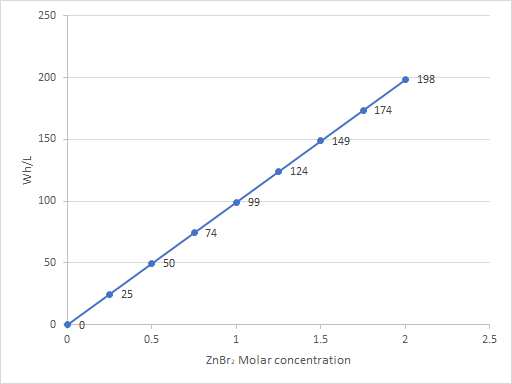

We know the diffusion coefficient of Br2 in propylene carbonate to be 3.41×10−6 cm2 s−1 (1) while the coefficient in water is 1.18×10−5 cm2 s−1 (2), this is in part because of the higher viscosity of the organic solvent. This means that diffusion of Br2 in propylene carbonate will be more than 5x slower, which might be enough to create a functional battery with limited self-discharge, especially if this coefficient can be reduced further with the addition of the quaternary ammonium salts.

Even if the creation of a battery using entirely propylene carbonate is not possible, it might be the case that a highly concentrated TMPhABr or TBABr solution in this solvent will be immiscible with a 3M solution of ZnBr2 in water. If this is the case then a split approach with a bottom organic solvent and a top aqueous solvent might be possible, although this will depend largely on what the final density values actually are.

In any case, I have now ordered some propylene carbonate and will be carrying out some tests with it during the next couple of weeks.